Part I. Philosophy

This is a case study about maximizing long-term profitability in asset-heavy low-margin businesses by creating scarcity for competitors while embracing one's own limits.

It will be published in an upcoming issue of Asphalt Pavement magazine.

The article was written by Sean Devine, Founder & CEO of XBE.

Part I. Philosophy

For asset-heavy businesses with high marginal costs (e.g. asphalt producer/pavers, heavy civil contractors, etc), sustained profitability depends on creating scarcity for competitors while embracing one’s own limits. While “good markets” are great, they don’t last forever.

“The world isn't fair, Calvin."

"I know Dad, but why isn't it ever unfair in my favor?”

― Bill Watterson, The Essential Calvin and Hobbes: A Calvin and Hobbes Treasury

For Fools rush in where Angels fear to tread.

― Alexander Pope, “An essay on criticism”, 1709

Create Their Scarcity

The only kind of infrastructure worth more than it costs is the kind that competitors couldn’t buy for the same price or that wouldn’t help them if they did. When capital is cheap, cost itself is not a deterrent.

When deploying capital, focus entirely on the relative advantage of the investment. Do not create identical capacity. Investments make you better when they make competitors worse. Undifferentiated capacity is a liability.

Gain exclusive license to technology. Acquire differentiated land. Merge with a competitor. Develop proprietary intellectual property. Build a values based culture. Buy or build what they can't. Competitive advantage is leading the market where competitors can't follow.

When pricing, market leaders must remember their advantage. When they forget, competitors won’t. A small competitor is only capable of wrecking the market with help. The market leader that took the bait started the problem. Pricing mistakes by market leaders echo.

Embrace Your Scarcity

In “good” and “bad” markets, competitive advantage can be attained by embracing scarcity while others seek abundance. More capacity than needed is too much. Room to breathe is prudent, but not enough for someone else to start a fire.

Operationally ignore advantages. Surplus crew, truck, manufacturing, and inventory capacity creates an umbrella for competitors. Your cushion is their springboard. If you don’t run out of capacity sometimes, you have too much.

Plan don't buffer. Bring the whole picture into view. Let everyone see. Create options. Quantify uncertainty.

Profitability is a function of advantage, not efficiency. Management has leverage over efficiency, not advantage. Tomorrow’s profits can be traded for today’s comfort. Equity depreciation follows peak profits.

Don’t forget to add all assets not in use to the denominator when calculating utilization. EBITDA is only part of the story. Buy to the trough. Rent to the peak. Benchmark with possibilities.

Part II. Case Study: Gallagher Asphalt

Gallagher Asphalt has been in business for over 90 years. Its excellent reputation for quality has helped maintain its position as a trusted supplier of asphalt pavement solutions for South Chicagoland even when the market became saturated with competitive capacity.

Once the great recession of 2008 hit, the competitive advantage that Gallagher once enjoyed wasn’t going to be enough for the company to thrive in a time of up-and-down demand, surplus capacity, and aggressive competition. While the market was experiencing a modest balance of work in both public and private construction markets, budgetary troubles in Illinois created a volatile outlook for infrastructure spending.

To prepare themselves to seize the opportunities and weather the infrastructure demand, Gallagher pursued a strategy of Operational Excellence Through Innovation by embracing limits and maximizing both people’s performance and asset utilization.

The operational transformation included the following changes:

- Invested in the XBE software platform to digitize, integrate, and optimize all planning activities in order to increase visibility and operational precision.

- Restructured management organization and trained the entire team on enhanced planning and continuous improvement processes.

- Divested surplus equipment and increased equipment reliability.

- Reduced size of owned truck fleet.

- Increased early-season demand to leverage underutilized plants.

- Increased cross-functional collaboration to maximize coordination and reduce resource buffering.

“We continue to achieve good results in a financially unstable market by doing more and better with less,” explained Will Gallagher. “As our visibility into all aspects of our operation increased, it became clear that we had capacity available just-in-case we needed it, but that we didn’t actually need it. Better visibility led to more understanding and confidence which led to better decisions and improved financial results. Now that the demand forecast is looking brighter, we’re positioned to increase both our volumes and profitability. The better we’ve gotten, the better we can get. Gallagher Asphalt has some big things in the pipeline. We’re thriving.”

Part III. Externalities

We’re no longer solely judged by the value that we put out in the world. Our excesses, especially as they relate to atmospheric CO₂ and other greenhouse gas emissions, are subject to regulation, tax, and judgment.

Embracing scarcity improves profits, and also reduces negative externalities including the carbon footprint of operations. For example, let’s calculate the impact of optimized planning and execution on the trucking-related carbon footprint of a typical paving operation.

The difference in trucking efficiency between an average paving operation and an optimized paving operation is approximately 10%. In other words, for every 100 trucks, 10 will not contribute to production.

To calculate the carbon footprint of the 10% we need to calculate the carbon impact of the unnecessary mobilization, and the unnecessary idling since the same number of trip miles would be required.

The average mobilization distance to and from the job site is approximately 50 miles per day per truck. A typical truck might work 200 days per year. Given 10% waste, that means that 20 days of mobilizations were unnecessary. At 5 miles per gallon, that’s 200 days x 10% waste x 50 miles per day / 5 miles per gallon = 200 gallons of diesel burned to mobilize unnecessarily. In addition, a typical truck burns 0.5 - 1.0 gallons of diesel per hour while idling. Assuming an 8 hour day, that’s 200 days x 8 hours per day x 10% waste x 0.75 gallons per idle hour = 120 gallons of diesel to idle unnecessarily. In total, the difference between average and optimized trucking is approximately 320 gallons of diesel consumed per year.

The carbon footprint of 1 gallon of diesel is 22.44 pounds of CO₂. Therefore, the cost of average trucking is approximately 22.44 pounds per gallon of diesel x 320 gallons of diesel = 7,180 pounds (3.6 tons) of CO₂ per truck. For a typical trucking fleet of 50 trucks supporting a paving operation, that’s 359,000 pounds (180 tons) of CO₂ emitted unnecessarily.

The average truck working 200 days hauls 24,000 tons per year. Given the average CO₂ per ton of asphalt of 0.0104, the carbon footprint of the average truck year is 250 tons. By optimizing trucking, the carbon footprint can be reduced ~1.5%.

Trucking is not the only significant contributor to carbon emissions. Others include the liquid asphalt content of the mix design, the distance from the aggregate source to the plant, the mode of transportation of the aggregate to the plant, the mix temperature, the aggregate moisture content, the asphalt production rate at the plant, the distance of the plant to the job site, and the maintenance strategy of the asphalt pavement itself.

In most cases, it costs less to emit less CO₂ — but you do need to think more.

Part IV. Scarcity Assessment

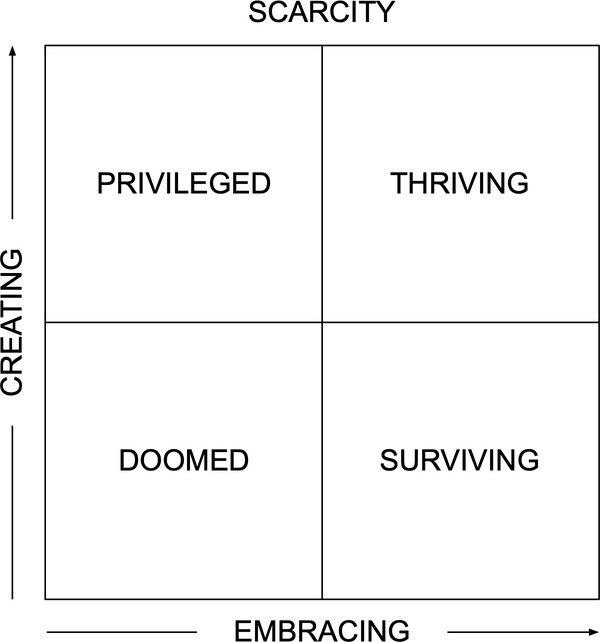

Look at the matrix below. Assess the degree to which your organization is creating competitive scarcity and embracing operational scarcity by comparing yourself to the philosophy for each dimension outlined in Part 1.

- Doomed: Organizations that have neither created scarcity for others nor embraced scarcity themselves are doomed to live off their balance sheet until it cannot support the replacement of their depreciating assets. Many doomed organizations were formerly privileged but sheltered new competitors under the umbrella of low asset utilization. Doomed organizations with a solid balance sheet can theoretically turn it around, but seldom without leadership or ownership changes.

- Surviving: Organizations that have embraced their own limits as a means to generate cost advantage can survive even in very difficult market conditions. As they bide their time, these organizations should be on the hunt to invest in infrastructure (e.g. vertical integration, differentiated technology, market intelligence, etc) that is unavailable to their competitors.

- Privileged: Organizations that are complacent in their current advantage will gradually drift towards the doomed quadrant. Only by seeing a more challenging future will the privileged organization embrace scarcity, invest in new capabilities, and ultimately thrive.

- Thriving: Advantaged organizations that continue to create scarcity for competitors while embracing their own scarcity operationally will thrive but never feel comfortable. To stay in this quadrant, the organization must embrace the constant struggle.

Part V. Conclusion

Value is scarcity — sometimes yours, sometimes theirs.

The most thought-provoking thing in our thought-provoking time is that we still are not thinking.

— Martin Heidegger, "What Calls for Thinking"

A plan is just a thought.

— Joseph Goldstein

We have to stop and think it through.

— Cookie Monster, "Smart Cookies Must Stop the Crumb"